Training 3D Narratives

By Kelly Gillikin Schoueri, PhD Candidate, Maastricht University

Last year, the PURE3D project team hosted a number of events surrounding the authoring of 3D heritage assets using Smithsonian’s Voyager Story. These activities sought to offer a balance between training both the technical skills of creating and editing 3D projects using Voyager Story as well as strategies of dealing with the conceptual challenges that are presented with interactive annotating of 3D heritage assets. The format of the workshop was iteratively reproduced first with Honours Course Students on the 25 Northumberland Road Voyager Presentation. We then adapted this training for the PURE3D Pilot Partners to get them started on narrating their 3D projects. Finally, a week-long workshop was held at Tokyo University for participants who wanted to use 3D and the Voyager system to develop disciplinary educational material. Our experiences with this wide range of participants not only deepened our own understanding and skills with the affordances and limitations of Voyager but it also presented opportunities to engage with a wide range of diverse 3D projects, each with their own unique stories to tell. A condensed version of this workshop will be held at the Computer Applications in Archaeology (CAA) 2023 Conference, registration is possible until March 26.

What is Voyager Story?

Voyager Story is the back-end editing interface behind the front-end 3D web viewer referred to as Voyager Explorer. In other words, Voyager Story is what the 3D editor uses to develop the 3D digital narrative and Voyager Explorer is what the end-user will see when they experience these narratives online. Formerly known as Smithsonian X3D, the system was co-created with Autodesk and the Smithsonian Digitization Program Office as a way to interactively distribute and educate online viewers about the 3D digitized collections of the Smithsonian Institution. Today, the Voyager suite of tools (including Cook for 3D data processor, Voyager Story, Voyager Explorer and Voyager Standalone) are all open-source and publicly available on the DPO Github page. Voyager Story is a flexible and user-friendly system that allows 3D editors to create:

- Annotation Labels: expandable hotspot annotations that are spatially aware;

- Articles: HTML-based pages with text and multimedia that can either overlay the 3D model or be situated to the side of it;

- Guided Tours: A flexible combination of annotation, articles, camera movements and a set of analysis features, such as alternative material shaders, light settings measuring tape and slicer tool (Smithsonian, 2023).

Tree of Life Smithsonian Voyager Explorer example

Workshop Format

The format of the workshop began first with an exercise on identifying the target audience for the Voyager presentation. Participants were asked to create Audience Persona profiles of potential users. These profiles included why they might be interested in the cultural heritage content and why accessing the content using 3D and the Voyager Explorer interface might enrich their experience with the content.

The second task for the participants involved a step-by-step tutorial exercise using the example of 25 Northumberland Road. The objective was to introduce the Voyager Story interface to the participants, making them: 1. comfortable with using the 3D editing system; and 2. exposing them to a few of the non-obvious possibilities provided by Voyager Story. Participants learned a number of basic tasks in Voyager Story, including how to:

- rename the project;

- upload multimedia to the Voyager Story workspace such as images and videos;

- create annotations and place them in the scene and change their properties;

- create and edit articles;

- link articles to annotations so that annotation content is dynamically integrated;

- merge the annotations, articles and camera movements into a short guided tour;

- embed interactive content from third-party websites, such as 3D models from Sketchfab and a google maps location.

PURE3D Infographic for Voyager Story Tutorial

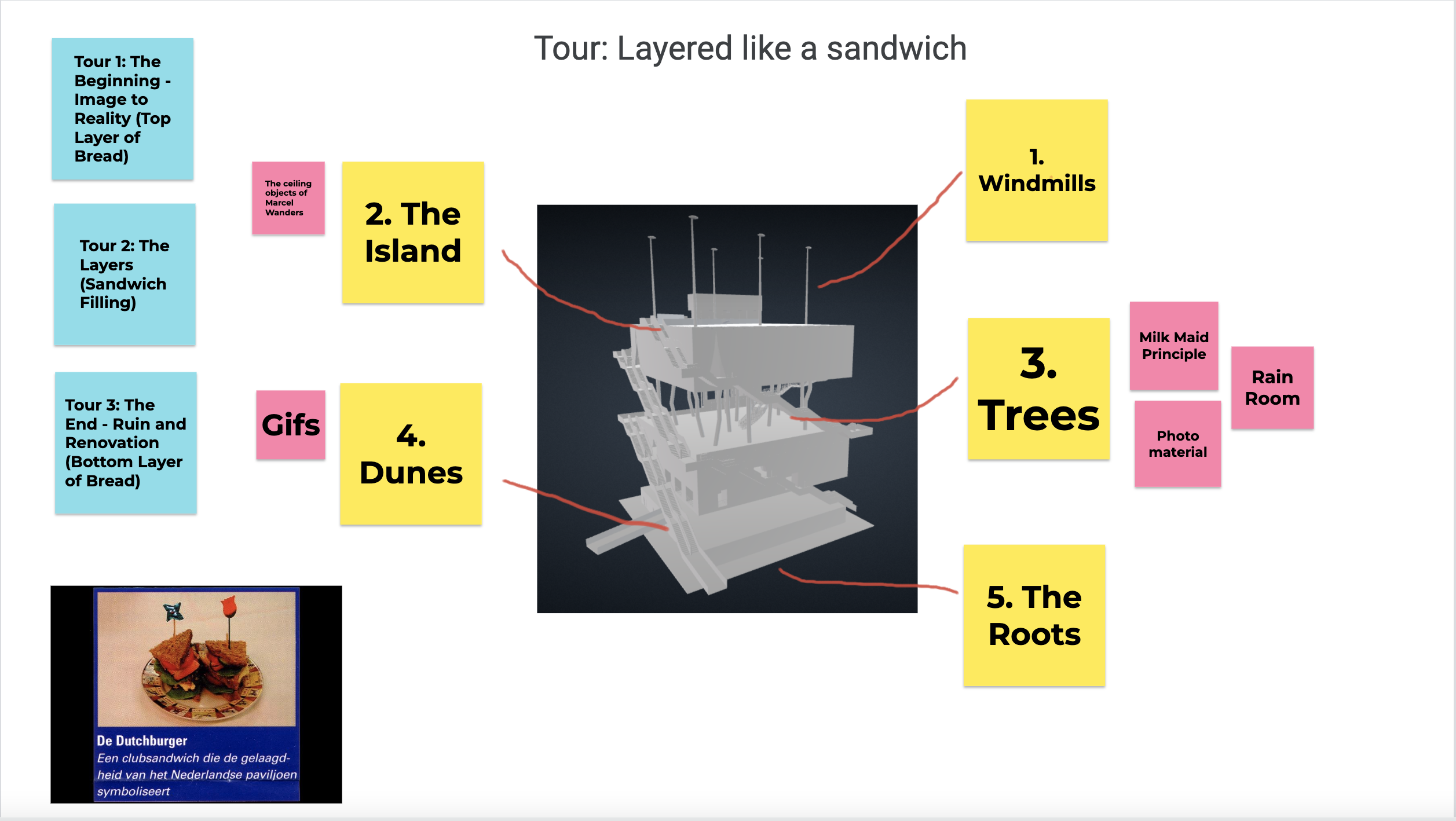

Brainstorm in Google Jamboard for 3D presentation of Hannover 2000

Once all participants completed the Voyager Story tutorial, we asked them to start brainstorming about their ideas for their own Voyager implementations. We set them up with a Google Jamboard workspace to get them started on thinking about what elements of their 3D model could be identified using the hotspot annotation label as well as which topics might be covered in an article. They were also asked to start thinking about how these might come together into a thematic guided tour.

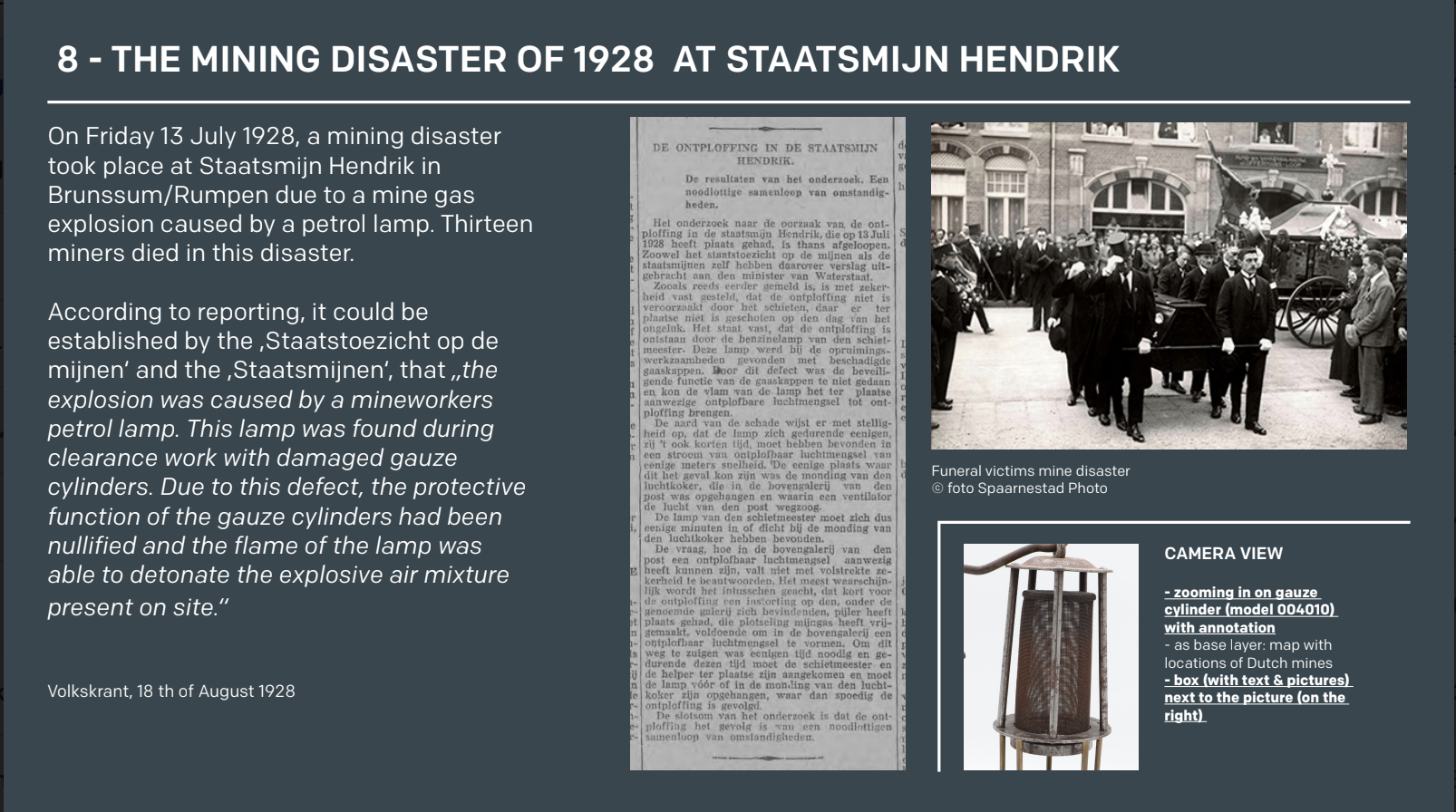

The final activity of the workshop was to set up homework based on the brainstorming exercise. We felt a framework for mapping out the articles and tours using Google Slides was the best way to prepare the content and materials before it went into Voyager. In this framework, each slide represents an article and should include: a title, a short text ranging from 200-500 words and some kind of multimedia to complement the text, e.g., images, videos, audios, other 3D models, etc. We recommended that the slides be organized in the order in which the guided tour would flow. It was also suggested that each tour begins with an introduction to the object/project and ends with a works cited and acknowledgements page.

Article Planning slide for 3D presentation of Potlamp from Nederlands Mijnmuseum

For the pilot partners participant group, we gave them some months to prepare their article content with the texts and multimedia. Afterwards, in November 2022, we then gathered together again for a Voyager Hack-a-Thon to implement these materials into their respective Voyager presentations. The event concluded with a show and tell of all the participants’ work as well as mentioning any challenges they encountered in their work process.

Challenges

The organization and implementation of the workshop was a learning experience for our PURE3D project team as well. The Voyager system itself, as a rich and complex tool, was at times challenging to fully utilize and there were sometimes bugs that we discovered. Thankfully, the Voyager development team at the Smithsonian DPO offered us a great deal of support and help in responding to emails and Github issues.

Beyond technical challenges, we encountered a range of conceptual issues, each unique to individual 3D models, projects and goals. One of the major challenges for participants was to determine what kind of content would be: 1. sufficient to create a detailed and robust narrative; and 2. relevant for the 3D model being presented.Based on the diversity of pilot projects, we discovered that single digitized objects presented the challenge of not always having enough to say using only the materiality of the object while the reconstructed buildings perhaps had so much it became overwhelming on where to begin.

For the case of single objects within a larger collection we found that narratives just on the physical material properties of the object itself were not suitable for a rich 3D narrative. It was suggested that an overarching theme connect and contextualize the individual objects and that each object would be used as an occasion to speak to a certain topic within that theme. For example, with our participants at the Nederlands Mine Museum, the overarching theme for the mining lamps was the technological evolution of the lamps as a way to frame and contextualize the history of coal mining. This approach reveals how mining lamp innovation is an integral part of the larger story linked to the lives of miners. For example, advancements in lamp technology with brighter light or fuel changes from oil to petrol to battery made working in the coal mine easier and safer over time.

For 3D projects of reconstructed buildings, we found that the greatest challenge was discovering how to deal with an overabundance of information. Heritage buildings are rich sources of stories, you could discuss, for example, the architectural history and features of a building, the function of the building and its known occupants or the evidence that was used in the process of creating that 3D reconstruction. We found that the Voyager capabilities of multiple guided tours helps to segment these various topics of 3D reconstruction. Additionally, the Voyager feature of tagging annotations was found to be very useful in segmenting annotations into topical groups so that a user isn’t overwhelmed with annotation labels overcrowding the 3D scene.

The final challenge we encountered in these training workshops was the importance of keeping the 3D model central to the story being told. Within Voyager, this meant that the tour should be balanced out with camera movements around the 3D object or scene as well as content-rich articles and/or pop-up annotations. In some cases, this was not an easy task to accomplish because oftentimes the content of the article doesn’t speak directly to a location or vantage point on the 3D model. We found that this was OK in small doses as long as the entire presentation wasn’t just a Powerpoint-like slideshow overlaying the 3D model in the background. In Voyager Story, you can set articles as either a pop–up overlay or you can offset it to either side of the viewing space. Many participants chose to set articles to the right so that 3D interaction and detailed annotation could occur simultaneously.

Conclusion

These activities surrounding training the technical and conceptual aspects of annotating scholarly 3D content have been instrumental in informing strategies for understanding the unique challenges behind annotating and narrating 3D cultural heritage. Ultimately, we made two insights:

- Just like every piece of the world’s cultural heritage, each 3D project is unique and has to be accommodated for both the material life history of the real world object (existing or not) as well as the digital surrogate or reconstruction of that object.

- The 3D web viewing interface used to contextualize, annotate and narrate the object structures our approach to this 3D object. How we think about it, how we narrate it and how we understand its contribution to digital society is controlled by the viewing system itself.