A Genealogy of Home Cinema

This project offers a fascinating glimpse into the emergence of home cinema at the dawn of the twentieth century, focusing on two key technologies: the Kinora motion photography viewer (1896-1914) and the Pathé Baby 9.5mm film projector (1922-1930). These artefacts, housed within the media archaeological collection of the Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C2DH) at the University of Luxembourg, shed light on the early practices of viewing and screening moving images in domestic settings.

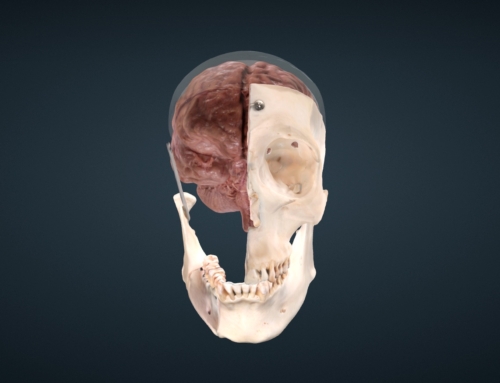

The 3D model of the Kinora was developed to deepen understanding of its materiality, functionality, and usage as a significant media historical object. Part of the Kinora 3D Replica project, which was a sub-project of the larger ‘Doing Experimental Media Archaeology: Practice & Theory’ initiative, this endeavour explored the heuristic value of hands-on approaches for media historical research. Through replication via 3D modelling and desktop manufacturing techniques, the aim is to unlock new insights into the Kinora’s technological features and user experiences.

The resulting 3D replicas, available on platforms like SketchFab and Europeana, were produced as part of the CRAFTED project. This initiative sought to document both material and immaterial forms of heritage within the realm of analogue media production. By making these replicas accessible online, the project aimed to facilitate broader engagement with these historical artefacts and their significance in shaping early home cinema experiences.

The proposed project for PURE 3D aims to present a historical narrative of early twentieth-century home cinema by synthesising the existing 3D models of the Kinora viewer and the Pathé Baby 9.5mm film projector. These technologies, with their distinct user practices, offer a comparative view of how individuals experienced moving images at home between 1900 and 1930. The Kinora, for instance, is a motion photography viewer which made use of a flip-book mechanism in which a series of paper-based photographic cards was attached to a wheel. By turning the wheel and looking through the viewer, one could watch the series of photographs in motion. It was invented in 1896 as an adapted version of the Mutoscope, which also functioned as an individual viewing machine. In that sense, the Kinora is reminiscent of the principles of 19th-century “pre-cinema” optical toys, like the Phenakistoscope and the Zoetrope, the chronophotographic experiments of Muybridge, Marey, and Friese-Greene, as well as related paper-based animated portrait photography systems, like the Biofix and Filoscope. All these 19th-century optical toys and early 20th-century animated photography systems provide an individual viewing experience of watching moving images.

The individual viewing experience can be contrasted with the collective viewing experience, which eventually became the dominant form of watching moving images in the 20th century. The Lumiere Cinématographe and other early film projection systems allowed for the projection of moving images on a large screen, thereby facilitating the collective viewing of moving images by an audience. In the first decades of the 20th century, various attempts were made to develop film projection systems for home use. However, most of these failed due to various reasons (costs, heavy equipment, safety). It was not until the early 1920s that home cinema truly developed into a popular middle-class practice with the release of the Pathé Baby 9.5mm film projector in 1922 and the Kodascope 16mm film projector in 1923. These safety-film screening technologies would effectively bring “cinema into the home” (le cinéma chez soi), to reflect Pathé’s slogan at the time.

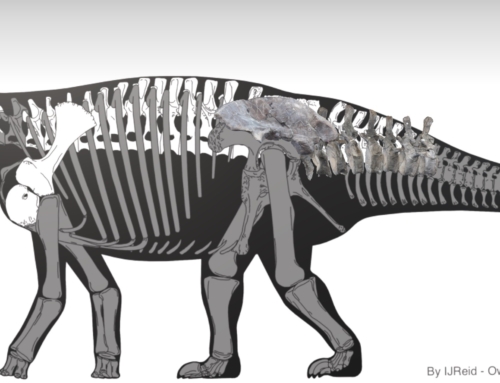

This project will not only present this historical narrative as a way to demonstrate the two contrasting types of home cinema technologies and their viewing experiences. It will also show their similarities and contextualise their historical continuities, for instance in terms of the frame rate of the moving image, the effective image size in screening practices and technological system (e.g. the worm gear mechanism of the Kinora showing similarities with the Pathé Baby internal mechanism). By means of the 3D models and “opening up” the technology in presenting specific parts of the mechanism, the project consequently aims to present an advanced 3D scholarly edition that reflects the historical trajectories and mechanical workings of the various technological objects in relation to their material affordances and historical contexts of use.

For more information see:

3D Scholarly Edition Author: Tim van der Heijden

Dr. Tim van der Heijden is a media historian with a special interest in the history of amateur media technologies and practices. He holds a Ph.D in media history from Maastricht University, an M.A. in media studies (research-master) from the University of Amsterdam, and a B.A. in cultural studies from Erasmus University Rotterdam.

His dissertation Hybrid Histories: Technologies of Memory and the Cultural Dynamics of Home Movies, 1895-2005 explores the home movie as a twentieth-century family memory practice from a long-term historical perspective. Specifically, it investigates how changes in technologies of memory (from film via video to digital media) have shaped new forms of home movie making and screening. It was written in the context of the research project Changing Platforms of Ritualized Memory Practices: The Cultural Dynamics of Home Movies (2012-2016), funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

In April 2017, he started working for the Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH) at the University of Luxembourg as a post-doctoral researcher and coordinator of the Doctoral Training Unit (DTU) Digital History and Hermeneutics, an interdisciplinary digital history project funded by the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR). From September 2019 until July 2021 he worked as a postdoctoral researcher within the FNR-funded project Doing Experimental Media Archaeology: Practice and Theory (DEMA).

In July 2021, he started a position as assistant professor of Media Studies at the Faculty of Humanities of the Open University in the Netherlands.