Dilemmas in Historical 3D Presentations: The Case of Maastricht 1748

by Eric P. G. Wetzels, Municipality of Maastricht

Historical presentations fascinate people. These people may be inhabitants of a historically investigated location, or they could be tourists, just passing through for a short while. Historical presentations often consist of reconstructions, which are the visualizations of research through the medium of 3D-models or even of old-fashioned storytelling. In that sense, every reconstruction is a combination of historical facts, current understanding of those facts, existing remains, new or old data, that can be either 2D or 3D, literature, archives or even oral history. All of this combined information presents an image of what we think history was. It is almost always a form of interpretation. For a good twenty years, digital storytelling has been used to combine different types of information and methods of presenting this information, such as audio-visual media as well as virtual and augmented realities.

While historical storytelling is needed for these reconstructions, it is this very technique that introduces a variety of dilemmas. These dilemmas may be invisible to the consumer’s eye but are easily noticeable for the researchers. In other words, the making of any reconstruction of a historical feature, period or event is always subject to debate and discussion. Practically no historical story is complete, however the nature of visual historical reconstruction is that they often require a realistic portrayal. Therefore, attempts to complete a historical or archaeological presentation is done with an incomplete or uncertain set of knowledge. However, this is not necessarily a problem, as long as it is made clear to the public in a transparent way that the historical presentation is just a reconstruction and not the reconstruction. Unfortunately, this is not an easy task, because what was once caught in the eye, remains in the eye. That is to say, a visual reconstruction is a compelling image that one may not easily get out of the mind. In many cases, it becomes ingrained!

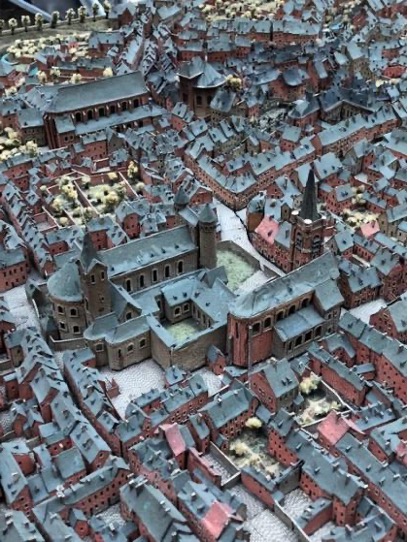

Maastricht as depicted on the model 1748

“History is often more constructed and reconstructed, than being researched. By introducing incomplete information into 3D projects, one reinforces the incorrect image that already exists.”

Use of History

“The use of history” is not a common phrase, but in many ways and by many different practitioners history is being used. It is used, most obviously, by archaeologists and historians, but much more intensely and publicly by politicians, marketing specialists, communication experts and people who want to prove something using historical examples. Even in international politics, history is used (or better: abused) to support claims on land, on wealth, on power and hierarchical positions.

Apart from this clear abuse, another form of un-historical use is noticeable. A common approach is to focus on extremes: the oldest, the first, the largest, the biggest, the smallest, the best, or the most expensive. But that is hardly ever a distinctive feature and never part of a contextual explanation–at least it shouldn’t be. Above all, it does not help to understand the essence of historical meaning.

A regional Limburg example may offer some insight: some years ago, local journalists and politicians argued whether Roman Heerlen was younger or older than Roman Maastricht. Both towns are separated some 20 kilometers from each other and differ in age for a decade or so. Being the oldest would mean … well, what would it mean? And who cares? Much more interesting is to try to explain the way in which these two towns were interrelated in Roman times. To describe their interdependency and their complementarity. Knowing that Maastricht functioned as the harbor for both Tongeren in the west and Heerlen in the east, teaches us more about how Maastricht was positioned in the Euregio, why it became what it was, and how euregional society functioned in Roman times. It tells us more about what were the distinctive features for Maastricht and the Euregio and how other historical features should be understood and interpreted. Therefore, the use of history should be considered carefully. For the Municipality of Maastricht, its contribution to the PURE3D project, means that useful data on Maastricht’s historical past should be combined carefully with known information and existing ideas.

The Maastricht case: The Claustral Belt around the Church of our Lady

PURE3D is a theoretical and practical research project, supported by case studies using different subject content and research techniques. The Municipality of Maastricht has been invited to produce one of these pilot cases. The chosen case is that of the claustral belt around the church of Our Lady, an area in the oldest part of modern Maastricht, dating back to pre-Roman times. Today, this location is where many entrepreneurs do their business. Residents stroll the streets where restaurants and tourists use the many terraces in the middle of the Square of Our Lady (Onze Lieve Vrouweplein, or Slevrouwweplein in the local language).

Photo by: Hans-Peter Schaeffer

What these people see is an empty and partly cobblestoned area with restaurant terraces, old houses and a medieval church. What they do not see is the historical depth of this location: in Roman times this was the border area of the small fortified castrum (castellum) with roads and defensive moats, the terraces are situated on an old burial place, the houses surrounding the square were built by the chapter of Our Lady as the claustral belt of the lords of this chapter and were in their possession for centuries. The 1000 years old church was used for a time in the early 19th century as a municipal depot for arms and gunpowder. These and many more stories need to be told to those who use the Square of Our Lady, whether they are residents, students or tourists.

Explanation of the Maastricht Case

Maastricht is a well-known archaeological and historical town, of which many people have heard, but only a few know about the city’s rich past. Maastricht is very well researched – thousands of books and hundreds of PhD theses have been written on the town’s history. Even so, a lot of research can still be done, especially within the context of its natural surroundings, the Euregio. However, Maastricht offers few visual historical presentations. The town itself functions as a scenery for local history and as reservoir of historical data. Only a small number of exhibitions and reconstructions are available for residents and tourists of this town.

As a part of the Euregional heritage project, Terra Mosana, the original 18th c. maquette of the town was 3D-scanned. This Maastricht Maquette, dating from 1748-1752, still exists (Musée des Beaux Arts in Lille/France) and provides a very detailed miniature model of Maastricht as it existed in 1748 – including the medieval town wall and the outer defense system. The 3D scan is now available, as well as details on the techniques used by the project . As part of the project, the historical data was also used to develop four augmented storylines using the 3D scan of the maquette: 1. a search for a guild membership, 2. the murder of a soldier at the gate to Tongeren, 3. a huge feast in the town after the siege of 1748, and 4. the quarrels of the Antonites in the late 18th c. In order to make an augmented version, the original 3D-scan was rebuilt as an animated model.

The Desired Effect of PURE3D for Maastricht

What we could do is combine, stack and visualize all sorts of materials and data on the history of Maastricht and present it to the public. However, this would be an enormous amount of information to consume (which people will forget) and is too complex to present in a suitable way. A better idea is to identify the desired outcomes and design a project that works towards those goals. So, what are the intended outcomes?

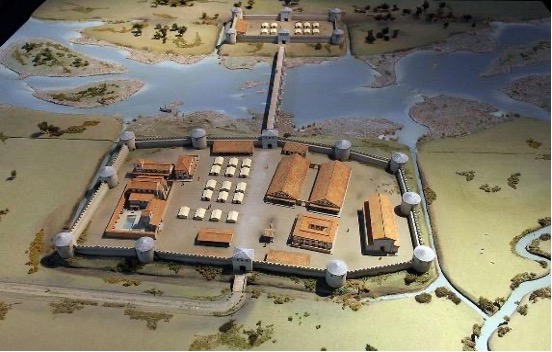

Roman Maastricht in the fourth century AD

First of all, we want to create an experience that demonstrates to the public that the current function of the Square of Our Lady is just a temporary one. The future is unknown; in the case of the square, there’s a possibility in which the terraces will one day disappear. If a chapter lord of the 17th c. could predict how we were to use this area of the city in the 21st c., he would have never come up with its current use of leisure and tourism. Therefore, the first intended outcome is to show people that urban functions change a lot through time. We would like to make people aware of their position in history–that we are just stewards (‘rentmeesters’) of a limited space, during a short period of time.

A second intended outcome is to show people the historical depth of this location. To give them a sense of the dynamic evolution of every town’s history and every person’s life. Executed in the right way, people could experience history from a formerly unknown perspective and, in so doing, get inspiration or enrich one’s life.

The third intended outcome could be to make the public more aware of their surroundings, by presenting them micro-doses of information in an accessible way. Information overload in this matter is a real struggle for public heritage consumers. Because of this, reducing and selecting information is a struggle for heritage professionals.

The fourth and final intended outcome is to create involvement and to have people realize that history, historical depth and cultural heritage can be consumed in either a passive or active way. Some people just want to hear, listen and enjoy heritage, others want to actively participate in it. Both forms are acceptable, as people are not all the same.

On all these intended outcomes, interventions can be related:

| Nr. | Intended Outcome/Goal: | Keywords | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Experience changing functions of geographic unites in time | Temporality | Experience humility |

| 2 | Sense of historical depth | Fascination-inspiration | Explain chronology |

| 3 | Make people aware through telling the story | Knowledge | Inform people on content |

| 4 | Get people involved, so they can experience and participate (respectively in a passive, or active way) | Involvement | Activate people and program their participation |

Intended-effect-matrix

As always, undesired effects also exist. Cultural heritage can be experienced as a burden, i.e., as an overload of information, the result of which people can no longer give their attention. It is necessary to find a balance between the right amount and the appropriate type of data. Beyond this, the presentation needs to be concise, clear and attractive. The most important undesired effect is when the historical presentation is restricted to colleague-specialists. When this happens, the importance of its use for society often disappears in detailed discussions and data-reservoirs.

Roman Maastricht in the second century AD

During PURE3D, numerous dilemmas will be encountered. Below are only three, for which solutions are required:

Dilemma 1: when archaeologists and historians present a story, this is often perceived by the consumers as the official history, instead of a personal perspective on something that could have happened in the past. How do we prevent people from believing entirely in a historical visual presentation? It is necessary to make clear that different perspectives are possible and that the presented one, is just one of these possibilities.

Dilemma 2: how to present incomplete information in a geographically restricted area? Archaeological features need archaeological and historical context, but how do you represent that context within the boundaries of a reconstruction? For the Maastricht case, archaeological remains must be interpreted within the larger archaeological and historical context. That context, however, might not be part of the smaller case study area.

Dilemma 3: the Maastricht case attempts to give the consumer the ability to time-travel through multiple millennia. However, practically every person looks at history using their modern lens – the ‘looking-back-perspective’. Telling and explaining the situation in Roman or Merovingian times, however, requires the capacity to erase everything one knows and sees in the current city. Today’s image is the result of history, not the starting point. Therefore, we need the ‘looking-forward-perspective’. With this in mind, how can we make people clear their minds from ingrained ideas?

An answer to these dilemmas will be formulated during the project and thoughts on this matter will be part of the approach.